Elements of Enterneering®/Organisation/Strategy

Terms like strategic management and corporate strategy are firmly anchored in corporate management. Nevertheless, in practice, operational issues often take precedence and dominate thought and action. For example, questions arise as to whether products are worthwhile, how work is being done on current projects, which customers are generating the most pressure, or where resources are currently scarce. When it comes to developing a maintainable strategy, however, the most important questions are where the most sustainable competitive advantages will lie in the future, whether the company is truly offering the right products and which key measures and resource blocks will determine the implementation plan for the coming years. The way in which these questions are addressed forms the cornerstone for successful strategic management and the implementation of a realistic, functional strategy.

Experience has shown that strategic management is more successful in companies where a conscious differentiation is made between strategic planning and operational planning. This applies at the content, process and, where appropriate, functional levels. There is a difference between strategic planning and operational planning in terms of designing the content and approach. The renowned economist Peter F. Drucker described the difference as strategic planning being able to be paraphrased as ‘doing the right things’, while operational planning involves ‘doing the things right’. Since it is necessary to first define what the ‘right things’ are, before it becomes possible to do them right, strategic planning (strategy) is upstream from operational planning (implementation).

It therefore stands to reason that, as part of the process of corporate management, strategic planning must take place before operational planning. It is important to understand that the details of operational planning are adjusted annually or throughout the year, while the cycle for renewing strategic planning is usually much longer. This is an aspect that, in practice, is often handled incorrectly. Ultimately, strategies are meant to be implemented operationally and not be constantly reworked.

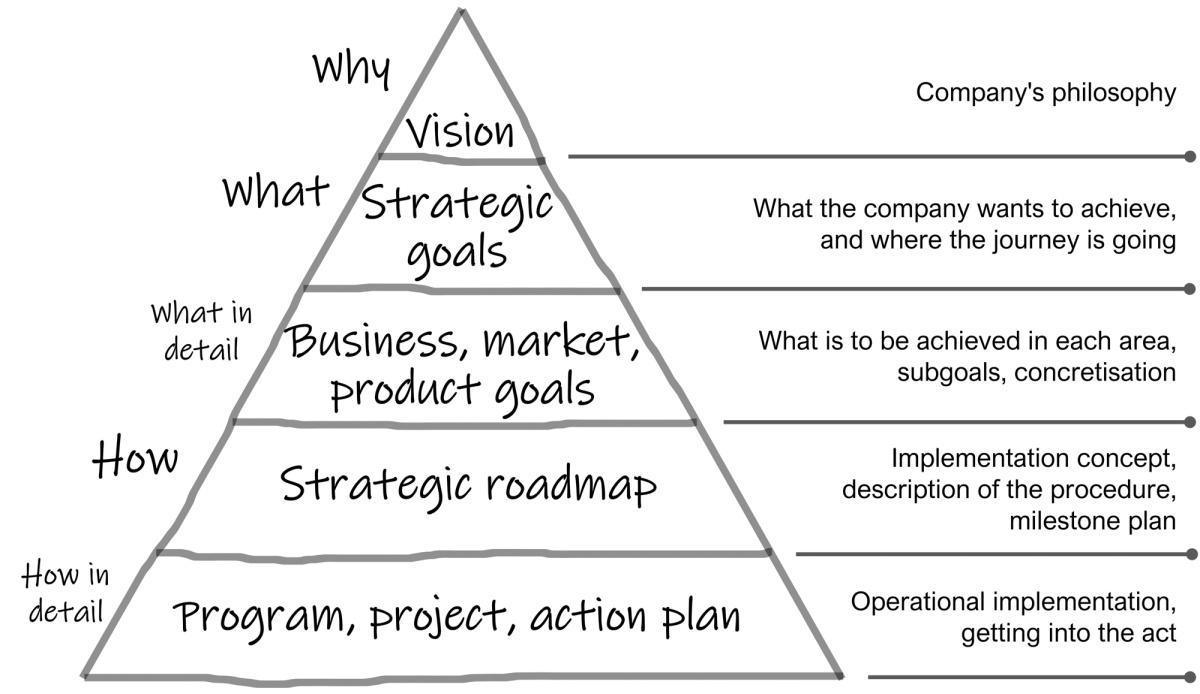

The aim of a holistic corporate strategy is to create meaningful goals that make the company’s ambitious yet achievable vision concrete, and, in turn, to support these goals with appropriate implementation steps. The corporate strategy thus contains a plan that defines the specific targets, steps and measures required to achieve the corporate vision. Based on a clear understanding of competitiveness, the corporate strategy sets out a multi-year roadmap for how best to leverage advantages to achieve profitable growth and strong, sustainable value creation. A successful corporate strategy determines the optimal business portfolio, prioritises the right value drivers and establishes resource allocation to translate the vision and goals into concrete actions that ultimately lead to measurable results and real value.

In other words, corporate strategy is a unique plan or framework, long-term in nature, and designed with the objective of gaining a competitive market advantage while delivering on promises to customers and stakeholders.

Another, much simpler, view of corporate strategy is to see it as a set of decisions and measures upon which a company bases its focus and actions for the future. Given that every organisation has a limited number of resources, the decision on how to prioritise the use of these resources will vary from company to company.

Without a clear corporate strategy, companies lose sight of their main objectives. Also, they lack the drive and focus a well-designed corporate strategy provides. A holistic strategy enables the company to establish practical performance and resource management. Finally, it serves as a kind of employee manual and clarification of the company’s plan for employees and external stakeholders. A corporate strategy in the 21st century should be framed in such a way that dynamic adjustments or corrections in response to unforeseen events are effectively possible.

In the area of people management, corporate strategy plays a key role in engaging, motivating and aligning employees. It aids in the optimal communication of the company's ideas, perceptions and intentions, enabling employees to clearly and measurably recognise, evaluate and optimise their contributions to the achievement of the corporate strategy. Especially in modern, agile and self-organised corporate structures, a well-functioning corporate strategy is an essential foundation for the success of the entire organisation.

THE PATH TO STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT

1. VISION, MISSION

In established companies, at least the vision statement, and ideally, the mission statement as well, should have been defined in the context of the corporate philosophy. If not, these would be the first tasks to accomplish on the path to strategy development.

2. STRATEGIC GOALS

From the point of view of corporate planning, a one- or two-sentence vision statement does not represent sufficiently formulated goals. The main characteristics of effective strategic goals are that they are clearly linked to the achievement of the corporate vision, that they are detailed enough to allow implementation measures and requirements to be derived, and that they are clearly measurable. When defining strategic goals, a direct link must be established to the market, the products, the customer benefits (added value), the company’s own competitive position and its organisation. This means it is important to not only know what achievements are desired but also to be able to assess the company’s position in the market environment.

In contrast to downstream goals (often called overall goals and sub-goals), strategic goals rarely focus on individual business units, products or markets. Strategic goals are usually higher-level goals that affect the entire company. Within the so-called target pyramid, they are therefore also at the top. Depending on the size and complexity of the company, strategic goals are subsequently underpinned by goals for individual markets, products or organisational units (business unit strategy, product strategy, etc.).

The most common tool for deriving strategic goals is probably the SWOT analysis [🡕]:

- S for Strengths – the company’s strengths and advantages in the market.

- W for Weaknesses – the company’s disadvantages or deficiencies in the market.

- O for Opportunities – market opportunities, options, timeframes.

- T for Threats – dangers, risks, restrictions.

Strategic goals are:

- Clearly understandable and success-specific.

- Ambitious yet achievable.

- Measurable and definable in terms of timeframes.

They are often defined in categories:

- Product and performance goals.

- Innovation and development goals.

- Organisational and resource goals.

The number of valid strategic goals must be limited to a reasonable and useful number, since the content of the goals will be broken down in further development of the strategy. If there are too many strategic goals, there is an acute risk of 'explosion' in terms of overall planning. A tried-and-tested approach for the sensible management of top-priority processes is to keep the goals in the single-digit range, i.e. less than 10.

3. CORE MEASURES

Core measures are overarching, robust bundles of measures necessary for achieving the strategic goals. In line with the SWOT analysis, this includes measures for seizing opportunities and possibilities, as well as for avoiding threats and reducing risks. In the process of developing these, it is essential to also consciously define core measures that map necessary further developments in the corporate organisation or culture. It is a common shortcoming in corporate practice that, within the strategy, organisational, structural or cultural measures are not planned and treated on par with business or product-related measures.

The art of deriving effective core measures involves:

- A belief that all the organisational units will achieve the strategic goals.

- No organisational unit thinking that the core measures are too detailed.

- More than 80% of the workforce understands what is meant by them.

- The ability to determine predecessor-successor relationships, schedule chains and needs.

A common tool used for visualising, planning and tracking core measures is the so-called 'strategic roadmap', that also identifies responsibilities.

4. RESOURCES

Strategic planning, including a vision, strategic goals and core measures, enables the estimate of dedicated resources with a view to successful strategy implementation. At the strategic planning level, it is not necessary to have precisely detailed plans or individual requirements. At this point, it is initially a matter of facilitating a gap analysis and determining rough demand figures. This is important not only for later operational planning but also for the evaluation of strategic feasibilities or obstacles. This rough estimate of resource requirements also supports the necessary focus on the most essential items that can be achieved with limited resources.

A strategic resource requirement is therefore not equivalent to a job requirement plan or individual investment budgets. These will be determined based on downstream planning activities.

5. PERFORMANCE

In the context of strategy, the topic of performance is often quoted, frequently desired and yet, repeatedly mapped inadequately. Performance indicators (KPIs) are often only derived directly from the formulation of the strategic goals. This is effective for determining achievement levels or doing a gap analysis of the strategic goals. However, it does not always suffice for identifying and analysing achievement, progress, and the possible need for correction with respect to the core measures.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) for measuring and evaluating strategic performance should:

- be related to the strategic objectives and the core measures,

- always enable a solid target-actual comparison, and

- be analysable throughout the year.

6. PLAN

The representation of the corporate strategy is the plan – although this is not a single document or source but usually consists of several parts. These parts include the profit and loss plan (P&L), the action plan (roadmap), the investment framework and the human resources framework. As with the roadmap, the focus of strategic planning is on overall numbers and framework budgets. All detailed downstream plans follow as part of operational planning (sub-goals, action plans/sprints or similar, liquidity plan, personnel development plan, etc.), which usually takes place after the strategy has been defined or periodically updated.

| Note on practical application In many organisations, there are clever people who, as dedicated actionists, tend to want to accurately apply approaches that are currently in vogue, or to make use of the most-frequently cited methods and tools. Here, prudent entrepreneurs are advised to give preference to the solutions that are most appropriate for their company, rather than to some theoretically accurate and comprehensive application. No company gains anything from dying in pursuit of beauty or perfectionism; gradual and sustainable development are what are called for. |

The art of strategic management is a targeted combination of the thinking involved in strategic and operational planning. This means operationalising the strategy in a structural and binding manner, i.e. making it implementable. This may sound banal, but in practice, it is frequently a failing. It is not uncommon to find that no link, or only an inadequate link, has been established between the creation of visualised strategy slides and the development of concrete operational action. In these cases, strategy reviews or annual reviews can quickly turn into journeys of discovery, on which actively controlled effects are rare occurrences.